I recently returned from my first three month trip to practice with Sharath Jois in Mysore. I am not a newcomer to the Ashtanga system – I completed the 4th series with my previous teacher Rolf Naujokat earlier in 2014, and have maintained a daily Ashtanga practice for nearly 12 years. I knew that when I went to Mysore for the first time, none of this would matter.

When I went to register at the beginning of my three months, Sharath asked me his standard question, “Who is your teacher?” I replied that I had been with Rolf for the past 8 years and first learned the system from Mark Darby a few years before that. Sharath didn’t ask which posture or series I had learned, nor did I volunteer this information; he had no further questions for me.

Regardless of a person’s background, Sharath has everyone start over from the beginning when they come to Mysore for the first time. There are good reasons for this. The way the practice has been taught in Mysore has changed over the years. The practice itself and the method remain the same, but one thing that has changed, and continues to change, is how quickly and under what circumstances people are taught new postures and series. Each Ashtanga teacher also has their own interpretation of how SKPJ or Sharath taught them.

Due to all this variation, the level of integrity in the practice of a first time student in Mysore can vary. Sharath takes everyone back to the beginning, and observes their practice based on his own standards.

What stood out to me right away is that Sharath has high standards, demanding great integrity from the students who come. These perhaps arise from Sharath’s own high standards that he sets for himself.

Sharath has been a part of the Ashtanga lineage in Mysore longer than any other living person. Although he was only a small boy when the first Western students came to practice in Mysore, he began his life in SKPJ’s house, and lived and breathed alongside his grandfather until his death. Sharath’s connection to the lineage is quite different from a few trips to Mysore – or even many trips – punctuating an otherwise separate life on the other side of the world.

Sharath has completed 25 years of “serious practice” as he calls it – not counting the years he learned asanas for fun before the age of 19. He has been teaching for nearly as long, and in recent years has taught hundreds of students per day, every day of his teaching season. Sharath witnessed firsthand how SKPJ’s teaching method changed over the years, and how different types of bodies and minds responded to those methods. He has spent 25 years applying his own evolving interpretation of the method to many different types of bodies and minds.

Sharath has also gone further in his own practice that anyone else in this lineage and system, and still maintains his daily personal practice in spite of having enormous personal responsibilities of family and institution.

Sharath Jois has had more direct experience with the practice on his own body, and in the bodies of thousands of students, than anyone else alive. His perspective on the practice is unique in its macro and universal, as well as micro and personal aspects.

For my own first trip in Mysore, Sharath had me do primary series only for the first three weeks. He began giving me intermediate series postures in the fourth week, one or two or three at time. He would wait for a few days or a week and then would give me the next set of postures. This started to become a familiar routine during the second month. At the end of the second month he told me to practice up to Eka Pada Sirsasana and the next day he instructed me to join the Led Intermediate class.

During my first Led Intermediate class, after completing Eka Pada Sirsasana I began to roll up my mat and make my way to the change room for finishing postures. As I stood up, Sharath came over and said “You try Dwi Pada”. I had to unroll my mat in a hurry, and was still setting it back up as Sharath started counting the five breaths for the posture. I quickly tried to zip myself into Dwi Pada. During the exiting Vinyasa, Sharath stood in front of me and said “You stop there”. I nodded in understanding and as I moved through upward and downward dog, he looked at me again and repeated for emphasis, “You stop there.”

I wasn’t surprised. Out of all four series that I have learned and practice, two of my most challenging postures are still in Intermediate series – Dwi Pada Sirsasana being one of them.

My previous teachers had deemed those postures to be good enough to move beyond, and for the past 7 years I have only been practicing Intermediate series once per week, devoting the main days of the week to practicing the 3rd and 4th series.

Although I have been well aware that two of my intermediate postures are not up to the standard of all my other postures, the fact that I only encounter them once per week has allowed me to avoid doing the necessary work to go deeper into them. When I would occasionally reflect on this, I would chalk it up to the fact that my 6 ft 3 body and its natural lordosis would not be capable of doing those two postures to the degree of perfection that I have observed other advanced practitioners doing. “Everyone has one or two weak postures”, I told myself. I continued to gloss over these posture in my once a week Intermediate practice.

While just about any other senior teacher would judge my Dwi Pada to be good enough, Sharath has higher standards. And even if it was good enough, Sharath knew that it could still improve.

“You stop there.”

Once he gave me that instruction, I knew the now familiar pattern of me getting new postures regularly was broken. There would be no new set of postures later that week, or the following week. In fact, he kept me on Dwi Pada for the entire third month until the end of my trip. I was not surprised. Each week, before the Monday Led Intermediate class, my girlfriend Susan would say “I think Sharath will move you on this week.” I would smile and say “We’ll see”.

It wasn’t so difficult for my ego to accept that I had been stopped in Intermediate series. I knew I wouldn’t get beyond Intermediate Series on my first trip, and expected my two challenging postures to be noticed by Sharath. What was difficult was that I had to actually do the work on Dwi Pada!

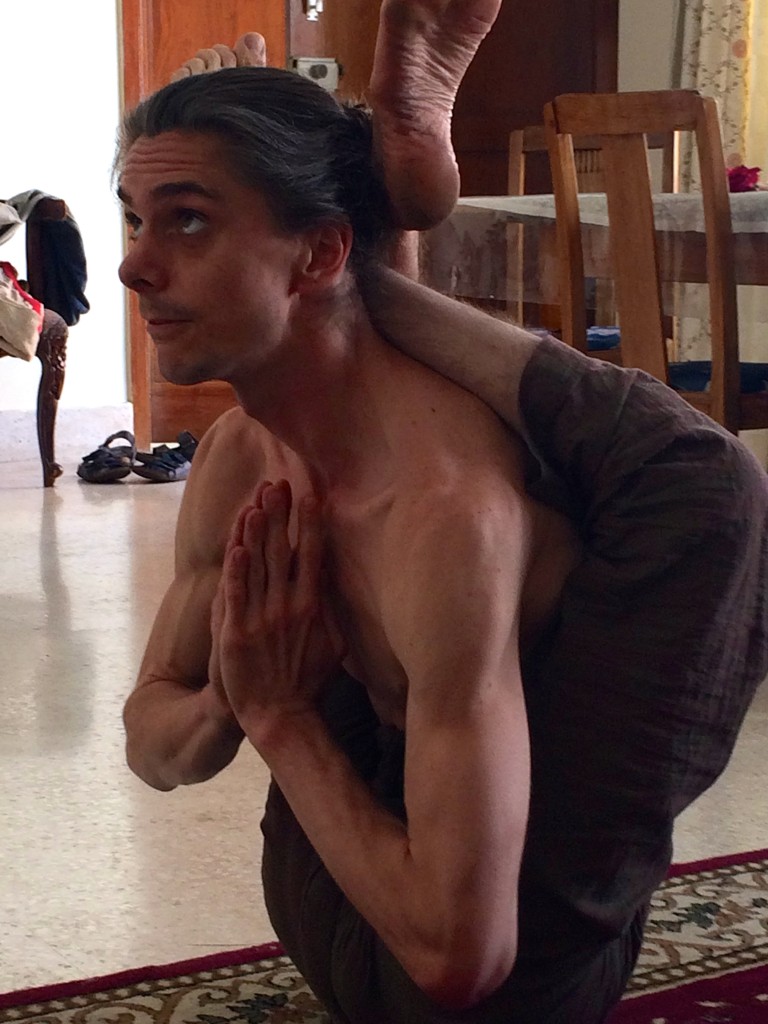

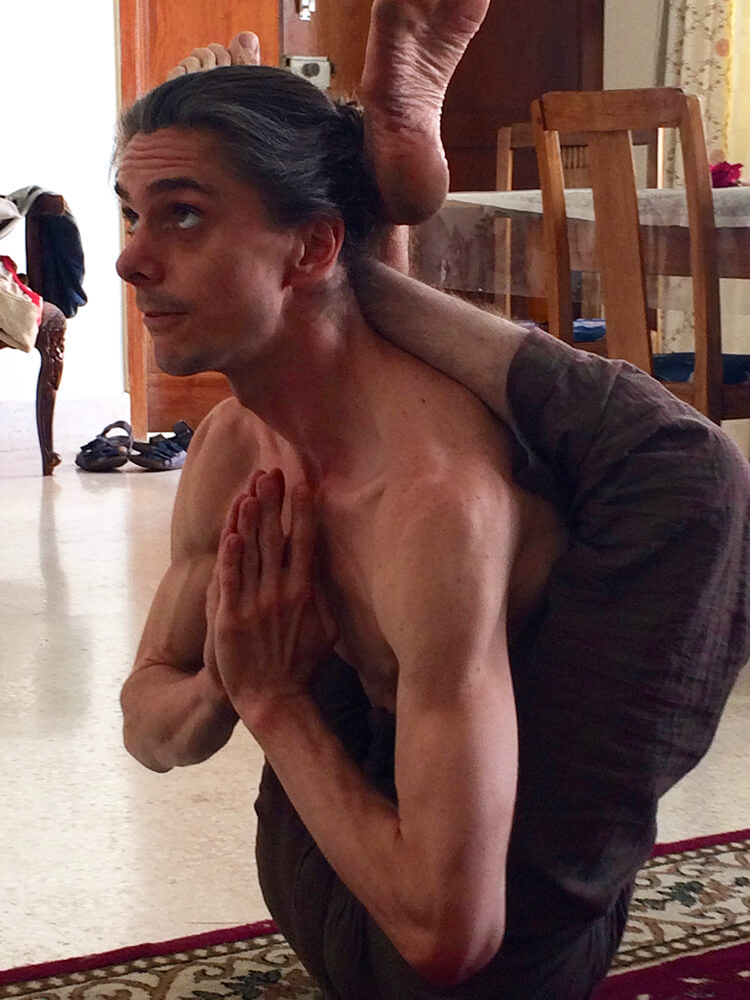

Nothing changed in my Dwi Pada for the next few days, so I decided to give it a little more examination at home. I asked Susan to adjust me more deeply into it, to the degree that I felt Sharath wanted me to be able to do on my own. She did this once or twice so I could get the feeling of the posture. We took before and after photos.

Dwi Pada Before

Dwi Pada After

For the rest of that week I played around with it at home, trying to find my way into what it felt like when I was adjusted more deeply by Susan. I started to have some degree of success in what I had previously considered to be impossible for my body. In class at the shala I would also spend more time on it, doing it 2 or 3 times before moving into my finishing postures. Within two weeks of Sharath’s “you stop there” instruction, my Dwi Pada had improved significantly and visibly. I could feel a whole new level of extension in my upper thoracic spine, ease in lifting my head, and evenness throughout my body.

Still, it was not yet as good as it could be. As I was leaving the shala after practice one morning, Sharath asked: “Iain – you did Dwi Pada?” “Yes”, I replied. “OK”, he smiled and left it at that.

It was during my third or fourth Led Intermediate class that Sharath came up behind me during Dwi Pada. “Lift your head more!” he exclaimed. I tried. “Iain – lift the head, spread your feet more!”. He half-heartedly pulled my left foot to the side. He clearly was not going to adjust me; he wanted me to do the work myself. As I rolled up my mat to leave after Dwi Pada, he again said “The head must be more up – spread the feet!” He looked perplexed, as if I was ignoring his instructions on purpose. “I’m trying”, I assured him.

Day by day, Dwi Pada became deeper and fuller. I no longer needed to play around with it at home outside of regular practice time, the transformation of the posture had taken on a life of its own and was steadily moving in a particular direction. In the three weeks since I have left Mysore, it has continued to improve, and the new state of the posture now feels very natural. It’s been so enjoyable for me to see the changes in a posture in which I previously assumed I had already reached my maximum potential, that I have continued to practice Intermediate series only instead of immediately going back to my regular 3rd and 4th series practices. It’s nice to spend some more time with what Sharath has taught me.

For this change to occur, I needed no technical instruction, and I only needed two adjustments from Susan. I didn’t need a two-hour workshop, breaking down the mechanics of the posture, or a special adjustment clinic. I didn’t need bodywork. I didn’t even need to be adjusted by Sharath in the posture. All I needed was to hear the words “You stop there” in order to begin to focus and develop the posture myself.

This clarifies and validates some of my understanding of how the Ashtanga system works, both as a practitioner and as a Mysore-style Ashtanga teacher.

I am now based in Ubud, Bali and I am exposed to a wide range of students, coming from all over the world and coming from many different teachers. This is quite interesting and a great experience for me. I can now understand much more clearly why Sharath takes everyone back to Primary Series when they start with him.

My perspective is that a significant percentage of students who come to practice with me are practicing further into the series than is appropriate for them. I have frequently felt the need to pull people back when they join practice with me, pointing out which postures they have not yet properly integrated or developed, and asking them to stop their practices there. Some students are quite open to this, some are not so happy. It’s a bit tricky as a teacher, to be able to do this in a compassionate way, so that it doesn’t feel like I am taking something away from the student. The reality is, I am giving them something, by showing them where they need to work.

By saying “you stop there” at Dwi Pada, Sharath didn’t take away the second half of intermediate, 3rd and 4th series away from me. I still have all those postures, and I can still practice them whenever I want (just not in Mysore yet). But what Sharath did is to give me Dwi Pada, and that is a real gift. By being asked to stop and do the work, I now feel what Dwi Pada should really feel like, for the first time – 11 or 12 years after I first learned it.

Having realized this, I am now finding it easier as a teacher to ask students to “stop there.” And if the student is receptive to it, within a matter of days, I can see, and they can also feel, how the posture I have stopped them on starts to transform and change.

There is also the potential to take this concept to an extreme and demand an ideal of perfection that is unattainable. As in anything else, it takes skill and experience to find the middle path, and to find the middle path with compassion. Becoming rigid and overly idealistic will be just as detrimental as being the opposite way.

Each student is an individual, and each individual has their own unique capacity for the different types of movements. As I worked on Dwi Pada in the shala in Mysore, I couldn’t help but look around and start to compare. Especially during Led Intermediate, I noticed that some of the people who were allowed to move on past Dwi Pada and do more postures were not doing Dwi Pada any better than I was. In fact, some were significantly worse than me.

I would sometimes grumble to Susan later in the day about this. She would remind me that they had probably also been stopped on Dwi Pada for some time, and that Sharath had eventually decided that they had reached their maximum potential and moved them on. “He knows that you can still do it better”, she told me. Of course, I knew she was right.

The act of stopping students at a particular posture in the Ashtanga system is not to force everyone to conform to a set standard, but to make sure that each individual develops the posture to their own maximum potential, in a way that is healthy for them.

This is why the standards are different for each individual. The expectations for Marichyasana D are going to be very different for an older person who has had 5 knee surgeries, compared to a younger person who is healthy, but just a bit stiff. The young and stiff person will likely be asked to stop there until they open up and can bind the posture, whereas the older person with damaged knees may be given different expectations.

It takes perceptiveness, skill, and experience on the part of a teacher to do this kind of analysis well. This is the correct application of the Ashtanga system, what I believe is the most important insight we as teachers should be trying to develop in ourselves.

It’s my observation that some Ashtanga teachers can get involved in other aspects of teaching at the expense of this insight. It’s especially easy to get caught up in teaching that makes the students feel good on a superficial level. Examples of this are giving great adjustments, giving students new postures, and displaying a lot of intellectual knowledge around the anatomy and physiology of the body and how it works in the postures.

When you hear praises being spoken about some Ashtanga teachers, often “he/she gives great adjustments” is a part of this description. And, almost everyone feels good when they come away from a few weeks with a senior teacher and have been given a bunch of new postures to work on. And, teachers who have a lot of intellectual understanding of anatomy and physiology, and can give long workshops discussing and expounding this understanding are also given a great deal of respect. These are all good recipes for popularity and influence for the teacher. It’s an understandable challenge for teachers to resist focusing on these aspects of teaching. The result, however, can be to lose perspective on what the actual point of the practice is.

Receiving a quality adjustment can be very transformative. In fact, it is often an essential ingredient in instigating a transformative process. As I mentioned earlier, when I started to explore Dwi Pada more, the first thing I did was ask Susan to adjust me more deeply into it, so I had a bodily experience to work towards. Getting a good adjustment can help to open things up, but more important it gives the mind and nervous system an organic experience of what the end result should FEEL like in the body, so that one can try to recreate it when working on one’s own.

Though I asked Susan to adjust me in Dwi Pada, I only needed her to adjust me two times. Once I had that experience, I knew my job was to then recreate it myself. It just gave me an understanding of what I was looking for. Sharath never attempted to adjust me in Dwi Pada. He merely verbalized in the simplest terms what was lacking in the posture, and then left it up to me to figure it out.

This is how the most skillful teachers will work with students – give them the minimum amount of input necessary for them to understand where they should be going, and then leave it up to them to work it out for themselves. This approach produces the strongest, most stable and most integrated result in the students, and it gives the students greater strength, confidence and power in the long run.

All good teachers know this. When I was practicing Iyengar yoga 15 years ago, I also had this experience. One day I was trying to do an arm balance, struggling and falling over again and again. My teacher (who also happened to be named Sharat) was standing a few feet away quietly watching me. After a lengthy period of time, one of the other students asked “Sharat, why won’t you help Iain?”. My teacher replied “as a teacher, you have to watch, and see how far your student can go”. This wisdom is there in all good teachers, from all traditions of yoga, and other forms of practice as well.

Over-adjusting takes power away from the students, and gives it to the teacher. The students become dependent on the teacher for those “great adjustments” to help them feel good. They never develop the ability to make themselves feel good. This dependency serves the teacher by giving them more popularity, student numbers and income, so it can be difficult for the teacher to resist giving out “great adjustments” like candy. I remember my first Iyengar teacher describing this dynamic. He said “I could give you all an amazing buzz in class every day, and make you addicted to me. I have the power to do this. But, my job is to teach you independence, so you can rely on yourselves. This is real yoga.”

Understanding of anatomy and physiology is also important. To know how the joints should be rotating, where a particular movement should and shouldn’t be coming from, what specific part of the body is actually stuck, and similar categories of knowledge are helpful and important, especially for protection against injury. But – they do not replace the real work that needs to be done to get unstuck.

Years ago I attended a couple of workshops with senior Ashtanga teachers. In these workshops, the teachers broke down the mechanics of Eka Pada and Dwi Pada. It was interesting and illuminating – intellectually. But, these workshops did not change my experience of Dwi Pada even slightly. I came away feeling like I had just spent hours with a teacher who had a lot of knowledge – but my Dwi Pada did not change one bit from it. Years later, it was only when Sharath told me, “You stop there” that I finally did the work to change my own Dwi Pada.

Teachers who give out a lot of new postures can also be very popular. Some students may attend a 2 or 4 week workshop or a few weeks of Mysore classes with a “posture-happy” teacher coming away with a handful of new postures to “work on,” whether the student is ready for them or not. At the same time, the teacher might be giving “great adjustments” in the difficult postures that are already part of the students’ practice repertoire — instead of stopping them there and asking them to work more deeply. This dynamic can breed misunderstanding of how the system works on the body-mind, what the job of the teacher is and what the goals of the practice actually are.

Other, less experienced teachers — with little or no traditional Ashtanga training — develop liberal interpretations of the Ashtanga method and offer Mysore style and Led classes under the Ashtanga name. These teachers are giving out as many postures as a student can handle without collapsing from exhaustion. The goal is to give a strong workout. The result is usually very little integration and a lot of pain and injury. This is also a gross misinterpretation of the method.

The Ashtanga practice is here to help us see where we are stuck. This can manifest on the physical, energetic, mental or emotional plane (or most likely all four at once). Stopping at the postures that force us to encounter where we are stuck is how we actually get to work through some of this, and this is how the practice transforms us as people – physically, energetically, emotionally, and mentally.

The very best Ashtanga teachers will be the ones who show us where we are stuck, and where we need to stop and do the work. The best Ashtanga teachers will be the ones who don’t keep giving us great adjustments every day, or spend hours explaining to us the anatomical details, or hand out new postures that we are not ready for. The best Ashtanga teachers will encourage or even force us to stop there, give us minimal guidance, and ask us to do it ourselves. This, in my humble opinion, is the role of the Mysore style Ashtanga teacher, and the correct application of the method.

Other language translations

- The Russian translation of this article can be found here. Thank you to Anna Glinko for the Russian translation.

Very interesting Iain. Very good points and insights. You nailed it.

It might be worth for you to know, since you are new to Mysore although not to the practice, that many senior teachers give out a lot of adjustments also because Guruji was teaching like that back then. Adjusting almost every pose. That’s how they were taught and they stayed with that. The teachings have evolved and refined in the years to follow with Guruji and continue to do so with Sharath. And about giving away a lot of poses: look at how Manju, Guruji’s own son, teaches. Exactly as you mentioned: letting students go on until they drop. He lets them decide for themselves where to stop… I know this from a student I had who is Manju’s student, not from my personal experience as I never practiced under his guidance. I completely align with Sharath’s method and have been teaching in the same strict format for several years now and continue to find it effective. As you said, he has more experience of anyone else in both practice and teaching, and has evolved his teaching to the very best. I am glad you got to understand it right away on your first trip to Mysore. Many who go at your level of practice most often experience frustration at the process. That’s also good, I guess. For each one the lesson he/she needs. My best wishes. Monica

Thank you Monica. I’ve heard the stories of how Guruji used to teach, and also met several students of Manju. My feeling is that Sharath has distilled the best of what the Ashtanga method has to offer and is now teaching it in a way that is very effective and safe, and possible for people to integrate and carry on for a lifetime of living in the world. I think that the term “research” in the old AYRI name was probably very relevant. I sense that Sharath has found the best formula, and as you said, continues to refine it as he himself learns more.

I feel quite fortunate to have finally arrived to practice in Mysore at this time in my life. If I had showed up there 15 years ago, it probably would have been more exciting, but far less beneficial for me as an overall person.

HI Ian,

Thanks for sharing your insight and experience.

Glad you mentioned the perspective of each student. Just because a teacher taught you postures in a particular way doesn’t mean it is the right path for every student that person teachers going forward. Perspective and refinement are good qualities for teachers and students. ‘stopping there’ offers the time to gain perspective and refinement.

Again, thank you for your teaching.

TOTALLY AGREE. It must have been a great experience. Thank you for sharing.

Beautiful, beautiful post. It’s so good to be reminded that the teacher’s job is ultimately to do as little as possible to make the student achieve as much as possible.

Thank you for sharing your experience.

Wow … agree with everything you say – there is so much truth there. And it inspires me to work harder where I am “stuck”. I wish more teachers would read this and simply watch their students rather than trying to be well-liked. Of course new students need a lot of help to begin with, but for people who know primary series and beyond…we just need to keep practicing, and definitely practice the poses that give us the most grief.

I’m still working on being able to drop back into a backbend from standing. It’s so easy to let a teacher stand there and spot me rather than face my own fears and just do it. When I was in Mysore, Sharath wouldn’t help me or come near me when it came time for dropbacks – he would simply yell “GO BACK” because he knew I could do it on my own. We’re so lucky to have him and to have teachers out there who are understand this method and are committed to it.

Jami, I had similar situation in Mysore, when I was working on my drop backs and Sharath helped me few times and one day he said that I have to do myself and I did it. But he didn’t tell me how should I do it so I was just dropping back and soon I ve got very bad lower back injury due to my drop backs and had to stop my practice for a long time. So I think that explanations how to go into the asana must be to prevent injuries at least, so here we need a bit of intellectual explanations from teachers (why we do this way but not the other way) and understanding from students. I teach now and I always explain students “how” and “why”.

what a relief to read your exhaustive explanation of the heart of the selfpractice style! having learned the same way as a student of radha and pierre in crete through the last 15 years, and being a mysore style astanga “sharer” ( im not certified, never been in mysore either), it is often so difficult and unpopular to do and say less (less adjustments, less asanas but practice practice practice!), especially when people around go for a weekend workshop with big names, come back with whole new series and plenty of tricks ( for the own ego)….nice thank you

Thank you for this honest report as I read your first article and wondered how it would all turn out for you. I myself just came back from Mysore and am rebuilding my practice. My teacher dished out postures to me before I was ready but I was also pretty adamant about doing them. In hindsight I am glad but now rebuilding after 10 years of practice. I am finding it refreshing as I am finding new things that I did not have before. I wondered what Sharath wanted from me and what he was looking for. I keep practicing and working to center and use the breath. And I think the biggest lesson from my last trip was that it was doing no good to judge myself and start enjoying the journey no matter how long it takes and how the road goes. I left Mysore with a just few postures into intermediate but now I feel like its right and right for me. I’m not sure how I would have felt it I did not get as far as I did but I’m fine for “stopping here”. Namaste.

Well written. Thank you. I particularly like your last paragraph…

…I have been going almost yearly to Mysore to study with Sharath (and previously SKJP) and in the early days, I also had a daily practice with a certified teacher in Australia who had given me more poses than what Sharath gave me in the shala. Interestingly, on one trip as Sharath went through a process of ‘giving back’ these postures, he held me in both my ‘worst’ posture and my ‘best’ posture in intermediate series. At the time I understood that I needed to go deeper in my weaker posture, but it took a little longer for me to work out why Sharath was holding me in what I thought was a posture that I was ‘good’ at. It actually took me about six months later after I had left Mysore to understand this. On one level, it was a great way to learn humility, it was also a way of learning that there is no such thing as perfection and that there is always something more to work on, and ultimately, it was also a way of Sharath showing me that he had more confidence in me than I had in myself, and with this I learnt to trust more (Sharath, the practice, myself, life…). In a more general sense, being held in my most comfortable pose and least comfortable pose, also showed me that the traditional Ashtanga Yoga practice is not about the physical – what the body can or can’t do isn’t important. Ultimately, each pose is the same, and it is important, even essential to detach from this physcial element.

Many aums

Great article thanks. I have been put off Ashtanga a bit more recently because of what I feel is an over-emphasis on achievement of asana – this often at the expense of the individual biomechanics and history of the student. I have been drawn to later Krishnamarchya style expressed through Desikachar and teach a form of hatha which just tries to find an effort/ease and presence balance with students. Nothing overly complex. The yoga comes to them rather than them coming to it. I now understand how Ashtanga can modify much more specifically to individuals and probably does at the source. That’s a really good thing to know and understand. Thanks for sharing it. It might bring me back to the practice again.

Hi Iain, I just wanted to comment on how well written this article is and how much I have taken from this. Thank you for taking the time to share your experience. I hope to see you in Bali. Take care.

Warm regards,

Quinn

Beautiful!

Yes, but I could not help but thinking ALL the way through this is the way it should be all the time and for every student of Yoga. This is how I learned and how I have continued to practice ‘on my own.’

Having studied under Shri K. Pattabi Jois when there were only 7 other students in the room, I remember very clearly him standing and watching and not giving me any physical adjustment. He only watched very quietly as if to see exactly what your teacher said about you, “to see how far you can go.” And later as I studied under Yogacharya Venkateha this was his method all the way, re: little input and letting me do the work.

I believe this is the way ALL Yoga needs to be taught not just Ashtanga. However, in the West people come with many assumptions, misconceptions and ideas about Yoga, teaching, teachers and how it is to be learned.

It is a real challenge NOT to succumb to: 1) giving all the adjustments ALL the time, 2) not letting students do whatever they want or have them practice beyond their means and 3) helping them to possibly unlearn both mental and physical habits that are not serving them in real growth.

To be honest, as a teacher you can do all of this, but you must also have a student who is willing to walk that walk with you.

It is a real challenge to teach like you are prescribing and I personally do not believe it can be done in workshops or classes of 50 plus people. For myself, I learned primary single-handedly from Guruji. I continued to learn in a very personal way from my other teachers. When you start to add more students it can be very difficult to see the individual and not get caught up in just trying to be popular, but really in being a great teacher.

This is how Guruji first started teaching. So yes, it is indeed true that everyone’s experience of the teaching and the learning process is extremely relative and varied. That’s why (and perhaps on a different note) it is a bit of a misconception when teachers try to immaculate what they teach as the REAL teachings. Or rather the ‘only’ way to teach that’s real.

The truth is there are many ways of teaching and the organic process is different from each teacher as they share the practice as they know it and to the student who receives it.

Thanks for taking the time to write and share your thoughts and experience. I totally agree with your insights about the practice and method of teaching/sharing it. Best Regards, Bela

Incorrect method

The old skool teachers, such as David WIlliams, Nancy Gilgoff, TIm Miller (etc, etc), each have at least 40 years of experience practice and teaching. So, saying such things as “Sharath has been a part of the Ashtanga lineage in Mysore longer than any other living person”, “Sharath has also gone further in his own practice that anyone else in this lineage and system”, and “Sharath Jois has had more direct experience with the practice on his own body, and in the bodies of thousands of students, than anyone else alive,” is simply misleading. To be quite frank, these are blatantly false claims. Anyone who has studied with Nancy Gilgoff (who used to watch Sharath run around the yoga room spraying students with water bottles when he was 5 years old) for the last 40 years will find these claims laughable. You just can’t print false facts.

Such sweeping statements not only make this article lack any credibility and integrity. They make it appear to be a sponsored-by-sharath PR campaign.

Its ok to be passionate and devoted to our teachers, but please post facts and not false claims.

Just saying.

Hi Dan,

Thanks for your comment. You bring up some interesting points to explore further.

When I say Sharath has been a part of the Ashtanga lineage longer than anyone, I am referring to multiple levels, beyond the asana practice. By taking birth in SKPJ’s house, Sharath was exposed, since birth to the entire lifestyle of a master yogi, including all the non-asana limbs of practice and lifestyle. Observing Sharath’s own lifestyle today — everything from his basic lifestyle choices to his consistency of practice — it is clear that he has absorbed and integrated all these other limbs for the duration of his life. Also, if one counts “time” in terms of say, number of hours with SKPJ, then there could not be anyone else who has spent more hours, more continuously with SKPJ than Sharath. That is why SKPJ passed the lineage on to Sharath, and not one of the old school Western teachers. As I said in the article, there is a big difference between making annual trips for a few months of the year, and living the life with SKPJ full time since birth.

I’ve never practiced with David, Nancy or Tim. I did meet one of them for a few minutes about 12 years ago. I was actually in Mysore when I met this person (though I was not practicing at the shala on that trip). Without naming which of the three it was – when I met this person, he/she was smoking a joint a few hours after his/her practice at KPJAYI. After 28 years of daily practice, if smoking a joint to relax (or for whatever other non medical reason) is still necessary, I would question how deeply the practice has been integrated into his/her life, and to what degree the other non-asana limbs have been assimilated and practiced, and what level of self mastery that person has attained.

I have no doubt at all that David, Nancy and Tim are excellent teachers. I have heard nothing but positive reports about one of them, and many positive reports about the other two. However, I would like to ask if any of them have been running a Mysore program continuously for the 40 years that they have been teaching? To my knowledge none of them teaches a daily Mysore program at present (though I could be wrong about this) – they seem to focus more on teaching workshops. Sharath has been teaching or assisting in a daily Mysore program for 6 months of the year for almost 25 years. Given that continuity, and given the number of students he has seen each day for that period of time, I think it is quite safe to say that Sharath has much more experience in terms of sheer numbers of students he has taught than any of the three teachers you have mentioned.

In terms of practice, Sharath completed the fifth series, as far as we know. I’m not sure whether it is known or not how far he got into sixth series. I am quite sure that no one else practiced that far, including the three teachers you have mentioned. And, while I have never seen any of these three teachers practice in person, I have seen videos of all three of them. I found that only one of the three had a practice that seemed to represent a lot of physical integrity and integration.

I don’t mean to discredit the practice or teachings of David, Nancy or Tim. Anyone who has practiced for 40 years has my full respect and is obviously doing something very right. And, I have absolutely no doubt that they all have much to offer as teachers. Nonetheless, due to the observations I have noted above, I would only consider one out of the three as someone that I felt I wanted to learn from, and if I had the choice between that person and Sharath, I would choose Sharath.

My article was not at all about “old school teachers” vs. Sharath. In fact, I learned to the end of the 4th series from an old school teacher (Rolf Naujokat), and will cherish this experience for the rest of my life. When I went to practice with Sharath for the first time this year, I was filled with natural awe and respect at the level of integrity he carries in every realm of his life, practice and teaching. He impressed me deeply. In my eyes he is truly a master teacher and has integrated and distilled all the elements of a yogic life and the physical Ashtanga Vinyasa practice. My article was about what I learned from him, which was mainly a validation of my own understanding of the Mysore method, gained through self study and self observation.

You sound like a typical pompous canadian. I would much rather learn yoga from someone who smokes a joint once in a while. You should have written this article in french so the rest of the world could have a good laugh at a google translation. And by the way, wasn’t that you i saw at the Crispy Duck diner in ubud?

@vieze you are a keyboard ninja, a true internet warrior…Wasn’t it you I saw at the Crispy Duck diner in ubud working furiously on your computer spewing out your venomous message here?

What you have written in this article is quite lovely and clearly you are devoted to Sharath, with very good reason. Your essay truly outlines the benefits and efficacy of the current Mysore teaching method, and I agree with most of what you say: I am all for letting students figure it out for themselves, eventually. But, as you say, all students are differently-abled – and teaching the practice is a huge responsibility and very difficult! I would say that most teachers you chide for giving “too many assists” are doing the best they can, Iain, with a great deal of loving kindness, and perhaps less ego than you imply.

No one is perfect. Not even Sharath.

Meanwhile, fyi, Tim and Nancy both run daily Mysore programs when they are in their home shalas. I can attest to this personally. They do not focus “more” on teaching workshops, but take some time each year to travel and teach. Most Ashtanga folks I know have a certain “wanderlust.” If Nancy and Tim also choose to couple a desire to travel with their love of teaching, well, why disparage their personal choice to share the teachings beyond their home shalas through these workshops, for persons who cannot or do not have the means to travel to learn from them (or with Sharath in India for that matter)? It implies that their choice is somewhat lacking in integrity. That’s a tad judgmental and a bit hypocritical, too, considering Sharath also travels and teaches around the world himself each year.

Hi Michelle,

Thanks for your thoughtful comments.

I didn’t mean to imply that teachers who give out too many adjustments or postures are necessarily acting from ego. I believe that most teachers are acting from a place of what they believe to the best for the students – but that it is also easy to get caught up in certain aspects of teaching that make students feel good on a more superficial level.

Regarding Nancy, Tim and David: I didn’t mean to imply that they lack integrity. Thank you for informing me that Tim and Nancy do run Mysore programs. My comments were mainly to counter the assertion that was made that any of them have more teaching and practice experience than Sharath. I was mainly trying to say that Sharath teaches more students, more continuously in Mysore style classes than anyone else. It wasn’t a judgement on the integrity of travelling and teaching.

I do feel that running a Mysore program that serves a particular community of regular students is a much more effective way to transmit the practice than teaching workshops. If one has the time and energy to do both, then great!

We all have to make judgments as we consider the important factors in decision making in life. I think the important thing is to analyze those factors from a place of objective clarity, rather than prejudice or bias. Then our judgments can be made well.

I agree, very much, that running a daily Mysore program is probably preferable to hone one’s teaching skills vs. travel teaching – preferable for the teacher, and preferable for their students. I can attest – I’ve run a Mysore program myself for the past 4+ years, with less than a couple of weeks off each year, and have seen how much it has benefited my students – and me: not just as a teacher, but in all areas of my life. (It’s become bhakti practice for me, actually – service and devotion!)

Meanwhile, as for “who has the most experience” – well, it’s really difficult for anyone besides the three of them (Sharath, Nancy or Tim) to say with any authority who has the most teaching experience. Of course, you’re forgetting Manju, – and, for that matter, Saraswati, Iain.

Frankly, I’d safely guess that none of them really care either way – so we shouldn’t either.

Whenever Ashtanga folks start to get into pissing contests over which teacher is the best, or the most knowledgable, or who teaches the “correct” method, I always feel a bit puzzled and saddened. Aren’t we trying to eradicate those negative thoughts? Honor the wise, right?

Many paths, one truth! 🙂

(I hope you don’t’ think I am singling you out with my last comment, Iain – I think we all have this propensity to defend our turf – to self-justify – in defense of our chosen path or creed. It’s human nature!)

Iain’s blog essay on the practice is very interesting to me. It’s fascinating to read about how a very experienced student interprets their own experience in a manner that conveys both the Jois lineage of Ashtanga Yoga and its systemic governing principles. And I’ve never seen anyone confront the means teacher’s use to establish themselves, which I appreciate. Iain, I believe you could flesh out this idea more critically; for example, you could as Canadian Matthew Remski (not an Ashtanga practitioner at all) does. He addresses how the economies of scale involved in the mass popularization of Yoga using a top-down, gym-like model for business. Maybe add more about the industry in the parts of the world where you live and teach. That said. I agree with Dan, too. To my ear, your statements about Sharath rang a wee bit false, and definitely felt like PR. Although as I compose my thoughts–I wonder–if this rhetoric is, quite simply, your own bow to the weight of your guru. Anyone who has your track record of practice (4th series with Rolf) has perhaps got to have the gift of a devotion that does not need to integrate critical thinking paradigms from the West. I applaud your journey, and thank you for sharing your experiences. You write about your journey with a generous breath of breadth and clarity!

I fully agree with you. The point is that people love gurus. They listen to them blindly, idolize and deify them. As Krishnamurti put it, gurus and disciples exploit each other… It is so easier to choose a guru that will incarnate the knowledge and the truth than to stand alone, make the effort to get conscious and make your road by yourself…

Most frequently gurus are gurus in dollars… The Mysore Ashtanga yoga institute is not an exception by any mean. It has been a tremendous cash machine for such a long time! Where is all this money going to? So much money is not spirituality but pure business.

Dan, I fully agree with you. The point is that people love gurus. They listen to them blindly, idolize and deify them. As Krishnamurti put it, gurus and disciples exploit each other… It is so easier to choose a guru that will incarnate the knowledge and the truth than to stand alone, make the effort to get conscious and make your road by yourself…

Most frequently gurus are gurus in dollars… The Mysore Ashtanga yoga institute is not an exception by any mean. It has been a tremendous cash machine for such a long time! Where is all this money going to? So much money is not spirituality but pure business.

PS: my comment is an answer to Dan, not to Alice!

Thank you for sharing your practice and learnings from Sharath in so much detail, Iain. Just wanted to let you know how much this article has moved me–since I discovered it online, I’ve been reading it every day. It is a good reminder to keep going with practice especially during the challenging asanas and during days when you just don’t want to. There is always some growth experienced on a daily basis, sometimes too subtle to be noticed but is there, and not necessarily limited to the asanas, as you have shown from your insights which can be applied to experiences off the mat. Please keep writing and inspiring! Namaste.

Hi Iain – your openness and sincerity are admirable. I too was impressed and inspired by Sharat’s integrity. I found your reflexions both insightful and interesting, especially on the qualities of a true yoga teacher. Your post reactivated a thought that’s often here as I contemplate my dharma in this life. Because a spiritual teacher’s role is ultimately to show his/her student that the truth is already abiding, and that nothing more than the bare essentials is needed to be truly happy, it seems to me that embracing this dharma (being a teacher of the Truth) means renouncing popularity and financial affluence all at once. Popular and wealthy yoga teachers invariably seem to play (consciously or not) upon the insatiable sense of lack that is sadly so distinctive of our conditioned minds. What are your thoughts on this – if any? Wishing you and Susan a great season in Ubud and looking forward to cross paths again. Love, Alice

Hi Alice,

It’s a good question – whether an authentic teacher who is really showing the way to deeper work needs to necessarily renounce popularity and wealth. I don’t think I have an answer or fully formed opinion on that. Some thoughts:

I consider yoga asana to be a wonderful tool for physical and mental health, introspection and self transformation – but not a complete path to spiritual realization in the context of the concept of enlightenment. I’m not sure I believe in enlightenment anymore.

As the majority of humans are not introspective by nature, any teaching that ask for intensive introspection will be a hard sell! Those who have managed to sell it well usually have found a way to make it somewhat entertaining – which is not necessarily a bad thing, if it reaches more people.

I think that anyone who is teaching an introspective technique that works, and teaches it well, will always have some truth seekers drawn to them. Probably enough to earn a reasonable amount of respect and income.

Those who find a way to make it more popular and become famous and wealthy probably encounter a whole host of other challenges in terms of keeping their own practice and integrity in line with their original intentions.

If I had the choice, I would probably prefer the challenges of livelihood over the challenges of popularity/wealth.

Alice, I fully agree with you. The point is that people love gurus. They listen to them blindly, idolize and deify them. As Krishnamurti put it, gurus and disciples exploit each other… It is so easier to choose a guru that will incarnate the knowledge and the truth than to stand alone, make the effort to get conscious and make your road by yourself…

Most frequently gurus are gurus in dollars… The Mysore Ashtanga yoga institute is not an exception by any mean. It has been a tremendous cash machine for such a long time! Where is all this money going to? So much money is not spirituality but pure business.

Hi Iain,

Feel greatly benefitted by your You Stop There post, and also the comments above. Am too inadequate to say anymore, just Thankssss for sharing..

I very much appreciate your sharing your experience and perspectives… I do have a question though- I personally have enjoyed how learning different poses improve my understanding and depth of earlier poses and have helped me see similarities and openings in different asana.

My teacher adjusts with questions (how can you use your hands to open the collar bone?) and encourages us to explore every pose. I feel I do all that level of required work in my entire practice, and I constantly work on everything from the most basic to my most difficult.

Is there no benefit to working on the whole series, with that same mindfulness and devotion, doing your best each day and continuing to dig and explore and never gloss over and accept as good enough? Also, being 48 yrs old I find my body will give out at certain areas – pain in spine, knees, hands – if I get too repetitious..

Interested in your thoughts. Many thanks

Hi Denise,

I feel that Ashtanga Vinyasa is a form of structural bodywork. The repetitive inputs of the sequences, done each day over a long period of time, are designed to slowly change and transform the very structure of the body and nervous system of the practitioner. My experience is that for these inputs to be integrated in a way that is sustainable and healthy, it needs to be done step by step. Too many inputs all at once (ie. learning an entire series or large section of asanas quickly) will overwhelm the system and it can break down instead of shifting in a healthy way that is integrated well into the body and life of the practitioner. The deeper one is practicing, the more true this is.

In a different style or method of yoga, this may not apply, but in terms of a daily Ashtanga practice, I feel it does apply to 99 percent of people. Too much, too quickly, leads to bad results eventually (or at least an unnecessarily painful time in arriving at the good results). I have had several personal experiences of this.

It is true that learning new postures will deepen the understanding and experience of previous postures or series, and really, we are always working on all the postures, whether we learned them 15 years ago, or just yesterday. “Mastery” is only relative, and I don’t think there are any postures that I don’t still learn things about on a regular basis.

I think if repetitious movements are causing pain, then one is either practicing beyond what is appropriate for one’s body, or something in the movements is not structurally sound in an alignment sense.

[…] Iain Grysak had a similar experience in Dwi Pada Sirsasana with Sharath: “He clearly was not going to adjust me; he wanted me to do the work myself…This is how the most skillful teachers will work with students – give them the minimum amount of input necessary for them to understand where they should be going, and then leave it up to them to work it out for themselves.” […]

Thank you so much for sharing your experience. I am currently in the middle of my second visit to Mysore to practice with Sharath. Last year I was here for 2 months and he moved me through to Intermediate Series in what seemed like a pretty quick pace, taking me up to supta vajrasana by the time I left. This year, he seemed to be doing the same, having me practice Primary for only 1 week before having me start back in on the Intermediate postures and having me join the led-Intermediate class the very next week after that. In a couple of short weeks (after starting to practice the Intermediate postures again), he had moved me up to the tittibasana sequence. But then, during the next Intermediate class, he had to give me a little assist in dwi pada to help me balance and then told me to stop there. I was floored. I had never had a teacher take away poses from me (except for when I had an injury). I told him that he already had me practicing up to tittibasana and then he said, “no, dwi pada is not correct. My mistake.” He didn’t seem upset or anything, and genuinely looked surprised to see that he had already given me the next postures. I was pretty upset about it at the time, and it was hard to let go of the excitement of moving through the series so quickly. But now, looking back, I remember feeling surprised that he moved me past it so quickly, because, like you, it has always been one of my most challenging postures; my own teacher at home held me stopped at that pose for quit some time. At home, with my teacher, I practice full Intermediate, so I still practice it every day. But being stopped at that posture puts all of the focus on it, and I, too, am learning a lot about that pose, simply by having to really work on it again; about the gross mechanics of it as well as the subtle aspects of it. It is also making me re-evaluate the practice and what it means to really “advance” in the practice and to learn more: does the learning and advancing come only when I get new postures, and when I progress through the series? Or is the learning happening, and the yoga practice still doing its work, whether or not I ever get another new posture? I am being reminded that the latter is the truth.

But, even though I know that, and that this is where the work is, it still sometimes feels discouraging to be “stuck” at that pose. To know that I have not received a new posture in 3 weeks, and that it is very likely that I will not receive any more postures for the remainder of my time here this year (until the end of March); and to know (from my practice at home) that I am capable of performing the other asanas in the series. So, it is heartening to hear about your experience, especially since you have been stopped at the same posture that I have. So, thank you, again, for sharing your experience and insights.

thanks Iain for taking the time to post and others for the dialogue – “You stop there” – Ultimately I am a lifelong beginner. Wherever I ‘stop’ psychically, emotionally, mentally, energetically or spiritually can be transformed through regular practice. What I take away from everyone’s post is that practice leads to transformation and teachers are our helpers. Iain taught me to ‘stop there’ over a decade ago and this was needed for me to release into understanding and appreciating the benefit of regular practice. Practice reaches beyond physical postures and mastering a particular series into life. Enjoy this beautiful day.

Hi Ian , very nice article !!

and is so good to heard, finally you was in mysore ,Sharath. is just an amaizing master,

Hugs my friend

M,

Very well written Iain. Thank you for sharing. I have practicing ashtanga for 4 years and during that time I don’t need Sharath to stop me. Because 2 pregnancies have stop my practice before him hahaha..I think ashtanga practice teaches us to be humble. And if your teacher does not stop you, maybe the nature will stops you by sickness, aging or pregnancy like me! Being advance in the practice is a great thing but for me the most important thing is to be able keep continue your practice in any circumstances according to what your body tells you and needs. It was a great practice this morning, see you tomorrow!

@Iain Grysak, Hi I am Sukant I am practice-ing iyengar yoga From last two years and recently I realized by reading this article on your website, that though I am doing 50 postures of iyengar yoga system but i have not masterd one of them even. Well I am now planning to start Asthanga Yoga’s primary series,So my question is should I master Suryanamaskaras First before doing anything else in the series ?

Hi Sukant.

Thanks for your comment. The best way to proceed would be to seek a qualified Ashtanga teacher in order to teach you the primary series. This teacher will be able to observe your practice and judge what degree of “mastery” is necessary in order for you to move on and learn more of the series. Step by step, under the guidance of a good teacher will be the best way to proceed.

Having read this I thought it was extremely enlightening.

I appreciate you finding the time and effort to

put this informative article together. I once

again find myself spending way too much time both reading and

posting comments. But so what, it was still worth it!

Hi Iain,

I just finished a led intermediate series with Sharath. As part of his European tour he is in London this week. I never had the opportunity – yet – to go to Mysore because of work; so I guess I was expecting a lot from this workshop in London. I was so impatient to practice under Sharath’s count and experienced eyes. I was ‘preparing’ myself, recently putting (too) much more efforts in my practice, ahead of this particular week for me. Although, I knew he might stop me at one point, I definitely did not expect that he would stop me at Dwi Pada Sirsasana; I was definitely more concerned about Karandavasana for example.

The: “you go back” is actually a gift from Sharath and your two articles on “you stop there” helped me a lot to put back everything in perspective today. I wanted to deeply thank you for that.