“I’ve been studying low back pain for the last 50 years of my life and if anyone says they know where low back pain comes from, they’re full of shit”

– Alf Nachemson, quoted in the above video.

I agree with the message of this video completely. After watching it, I felt compelled to write more about my interpretation of pain, injury, pathology and healing, especially in the context of the Ashtanga Yoga practice.

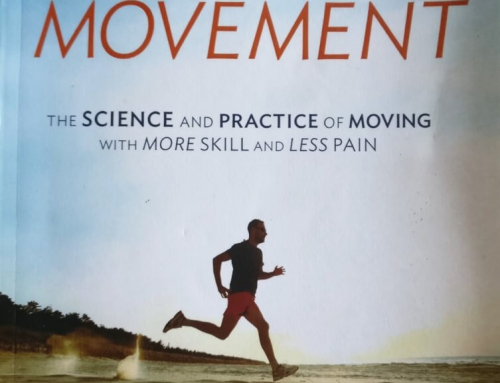

The structurally transformative process which arises from correct, long term application of the Ashtanga Yoga system of practice necessarily involves some experience of discomfort. Many practitioners don’t understand the inevitability of these unpleasant phases of the Ashtanga experience. Rather than accepting and patiently working through the discomfort using the method of practice, some practitioners immediately seek help from outside modalities in an attempt to eliminate the pain or discomfort as quickly as possible. Fortunately, the treatment they seek is usually not as dramatic as surgery, but the surgical tourism industry in countries like India does serve a number of Ashtangis who want a quick and easy diagnosis and treatment solution for their knee pain.

When a student reports pain to me, my general advice almost always falls along the lines of “Continue to practice. Back off somewhat, perhaps we’ll need to temporarily modify your practice, don’t push into the pain, but continue to practice.” Depending on the characteristics of the individual situation, I’ll probably have some more specific advice to go along with that, but in general terms that about covers it. With continued careful practice, if the pain doesn’t get worse, or it moves around to other areas of the body, or it spreads out, or it slowly improves, then I generally feel confident to tell the practitioner that they don’t need to do anything else. They shouldn’t seek other forms of manual therapy, nor do they need to consult a doctor and have medical scans. With continued intelligent and aware practice, it should work itself out and resolve itself.

The pain which arises out of daily, long term Ashtanga practice often represents a deeper reorganizing and recalibrating of the tension and structural patterns of the bones, tissues and fascia. This reorganization is actually a sign of correct practice and is a desirable result. Those who don’t want significant internal transformation shouldn’t practice this system of yoga.

Tension is an inherent property of a healthy human being, and of any stable structure in the universe. Tension is a necessary condition for life itself. Disorder and chaos are the path of least resistance (and least tension) in the universe. For a complex structure (whether it is a molecule, a human being, a society, or a solar system) to remain stable and not degenerate into chaos and disorder, some organized force – involving tension – is an essential property of the system. Complete elimination of tension is therefore not the goal of our practice. A human being that is free of all tension is a human being that has experienced death and disintegration. The component parts of the dead human being are free to disintegrate into chaos and disorder, until they are absorbed by other stable structural systems. Death is the only true state of freedom from tension.

The goal of our practice is to reorganize and recalibrate the tension patterns in our body-mind system so that we can have a more functional and stable relationship with the environment which we live in and are a part of. The state of bandha could be considered as the optimal state of tension for the human being. When opposing forces are balanced in bandha, the tension moves to the deepest “structural” layers of the body, such as the pelvic floor and the key supportive muscles for all of the joints, which are “designed” to hold us steady and stable in relationship to the earth and its field of gravity. In bandha, the tension is largely removed from the sleeve muscles, which are “designed” to be free and ready to respond to the need for movement. Hence the state of bandha is a dynamic balance between the forces of tension and release (or, bondage and freedom). This creates healthy and functional tensegrity patterning within the human structure. For me, this functional repatterning is the goal of asana practice.

We can think of ourselves as having two temporally distinct, but interconnected postural states. One of these states is the transient postural state which we happen to occupy at any given moment in time, throughout our daily lives. This is a relatively superficial and temporary postural state, and largely reflects a relatively temporary and superficial action (or inaction) of the muscles and tissues of our body. It is also reflective of our emotional state at that given moment. The other postural state which we can consider is the long term postural tendency, which reflects the deeper structural habits and patterns that we have adopted over our entire lives. This postural tendency is a cumulative result of the habits we generate through each of our transient postural states throughout our lives, along with the genetic tendencies which we are predisposed to from birth. This long term postural tendency could be thought of as a deeper and more crystallized (though not impossible to change) state of tension patterning within the human system.

Postural states reflect tensegrity patterns which organize the forces of tension and release within the body-mind structure. The momentary transient and the long term postural states influence and inform each other in a reciprocal relationship. Each momentary transient postural state provides an input into the human system which influences the more crystallized form of the long term postural tendency. If the transient state is similar in nature to the long term tendency, then the input of the transient state will strengthen and support the structure of the long term tendency. If, however, the transient state contains aspects which are different in nature from the long term tendency, then the input of the transient state will tend to induce a shift or change in the tensegrity patterning of the long term tendency. The causal relationship between the two types of postural state also flows the other way. The patterning of the long term tendency will also influence and inform how we hold ourselves in each momentary transient state.

In my view, the role of asana – vinyasa practice is to use conscious awareness in the transient postural states of each asana and vinyasa that we occupy during our daily practice, so that these transient postural states provide tensegrity patterning inputs which are healthier and more functional in nature than the patterning of our long term postural tendency. When this happens, the transient states of each asana and vinyasa of our practice encourage and induce a shift and transformation towards a healthier and more functional posture in the long term structural tendency.

When we do this day after day, using muscular strength, flexibility and awareness to provide the same repetitive tensegrity patterning inputs of the particular Ashtanga series that we are working on, the tensegrity patterns of the deeper structures of the human system, which reflect the longer term postural tendencies, eventually must shift and change in order to support the new transient movement patterns which we are regularly engaging in.

If we practice each posture and vinyasa with some degree of the balanced energetic state of bandha in place, then over time, our long term postural tendency will also tend to reflect the properties of bandha more naturally and readily. In a state of bandha we are in a more harmonious and functional relationship with the field of gravity. For example, when we stand in samasthiti with bandha in place, we tend to stand somewhat taller and more effectively spatially organized than we would if we were simply standing around, unaware of our posture. Practitioners who apply bandha well in each of the transient momentary postures (asanas and vinyasas) of their daily practice will actually grow taller over time. I have experienced this myself. My natural resting posture is now at least several centimeters taller than it was before I started daily yoga practice. I have also observed this happen in some long term students of mine.

This process of shifting and changing the long term structural tensegrity patterns of the body through asana practice is where the transformational pain arises, which many long term practitioners experience from time to time. The long term effects of shifting the deeper tensegrity patterns are healthy and beneficial, but the short term experience of getting from here to there can be uncomfortable. Imagine what has to change deep within the structural organization patterns of your body for you to grow taller. It is unlikely that this would happen without some pain or discomfort along the way.

Continued practice through these periods of discomfort is the best (and often the only) way to resolve this discomfort. By continuing to provide the inputs of the transient postural states of our daily practice, we encourage the patterning of the long term structural tendency to continue to evolve, until it eventually reaches a new stable conformation. There is an “intelligence” and functionality in the pain we are experiencing in this transition period. If we halt the process by stopping practice, or confuse the process by adding other, different inputs (such as resequencing the asanas, bodywork, manual therapy, surgery, etc), then the process gets sabotaged and in some cases this can make the pain worse, or simply transfer it to other parts of the body-mind system. If, however, we continue to provide the familiar inputs of our daily practice, the evolution in our long term postural tendency will continue to move with the intelligence of these familiar inputs of the Ashtanga series. Eventually, the longer term postural tendency will settle into a new, stable conformation. Once this new stable conformation is reached, the transformational pain generally subsides naturally. Sometimes the pain subsides gradually, getting a little bit weaker each day as the body continues to shift and stabilize into its new structural state. Sometime the pain disappears instantaneously, perhaps during some movement in our practice or perhaps while we are at rest later in the day.

Whether the pain dissipates gradually or instantaneously, it is continued practice (ie. continuing to provide the same transient structural inputs which have induced the shift) which will bring about this resolution. This advice can be counter intuitive to what many practitioners (and the general population) tend to believe. Upon experiencing pain most people tend to feel that they should A) stop practice for a while and B) consult a physician.

A physician will almost always prescribe rest and recommend avoiding yoga practice until things get better. For the reasons I have already mentioned, this will not likely provide effective long term resolution. A modern physician may also order x-rays and scans, which may confirm disc degeneration, herniation, or ligament, tendon or cartilage tears. As the above video states, a significant percentage of the “normal” population also have some or all of these “pathologies”, yet they don’t have any significant pain symptoms. Some degree of structural “pathology” is actually “normal”. Yet, if an Ashtanga practitioner (or anyone, whether they are a practitioner or not) who is in pain receives the news that their scans have confirmed some structural pathology, then the person will necessarily create a network of physical and psychological labels and restrictions around their pain. They will likely limit and restrict their practice and general life movements based on intellectual theories, rather than on phenomenological experience. The movements which they do allow themselves to perform will be done with fear and trepidation, with the anxiety of making their fragile condition worse. This mentality and set of physical restrictions will not promote healing in most cases.

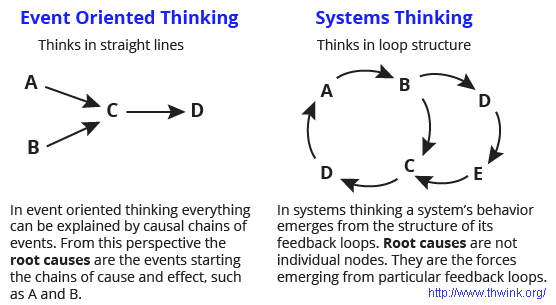

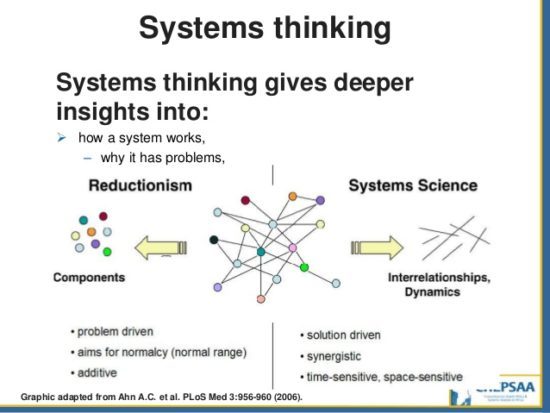

Ashtanga is a systems oriented type of practice. It is therefore important to try to understands its effects from a systems oriented perspective. The systems perspective of nature and the universe has begun to develop and evolve relatively recently. It is slowly gaining traction in the scientific community, and I believe that it is an accurate and realistic way to understand life and and the universe. It trumps the reductionist methodology which has been the pervading feature of both Western and Eastern approaches to understanding reality for most of the past several thousand years.

Reductionism attempts to understand something by breaking it down into its component parts and then examining the properties of those parts. It looks to the properties of the parts as being the root causes for the properties of the whole. This is what Western science has done for hundreds of years, and this is also what Eastern religions and philosophies, such as Buddhism, do. While both Western science and Buddhist philosophy have yielded accurate, valuable and useful perspectives on reality, they have not effectively explained everything that we experience.

Reductionism is also frequently used to analyze and understand asana practice and its effects on the human system. One of the most well known asana reductionists was BKS Iyengar. Mr. Iyengar took the Ashtanga system, which he learned from Krishnamacharya, and analytically broke it down into its component parts. He took the asanas out of their systematic relationships with one another through the vinyasa system, and turned each asana into a system of its own. He then took each individual asana, and broke it down into its component parts of the actions of each individual muscle, bone, etc. He then noted the effects on each individual body part in each individual asana, and how these effects contributed to the overall functioning and health of the human being. Not surprisingly, Mr. Iyengar’s work became of great interest to the modern medical community, which operates on the same reductionist paradigm.

Mr. Iyengar was a great innovator, and his work certainly yielded some valuable results and perspective. However, some important results and perspective were also lost through his abandonment of the systems view of Ashtanga Yoga. My own personal journey, from being trained as an Iyengar practitioner and teacher to becoming an Ashtanga practitioner and teacher, is that the systems perspective and experience of Ashtanga practice is deeper, richer, and more encompassing than the reductionist Iyengar technique. I value my experience with Iyengar Yoga. I am glad that I had it for four years in the beginning of my yoga journey, but there is a reason that I have been a daily Ashtanga practitioner for the subsequent 14 years. People sometimes tell me that they are drawn to me as teacher because I have an “Iyengar background” and they want that focus on alignment. My response to them is that the two systems are actually incompatible, and cannot be practiced together. I don’t use any alignment principles, props, or techniques from my Iyengar training in my Ashtanga practice and teaching. Alignment is certainly a feature of the Ashtanga system, but it is a very different perspective on alignment. In the Ashtanga practice, alignment is integrated into a systems perspective and experience.

Returning to pain and pathology, an example of a reductionist approach to pain experienced by an asana practitioner might be to obtain medical scans or use other diagnostic methods to find some pathology in one particular muscle, joint, ligament, etc. Upon discovering (or theorizing) some localized pathology, the experience of pain in asana practice would be understood to be directly caused by that pathology. The treatment would then be to remove that pathology – either through surgery, or less dramatically, through some form of deep tissue release or targeted manual therapy. There would also likely be a number of significant changes made to the person’s asana practice, based on the diagnosis of pathology in some body part.

Another reductionist approach in asana could be exemplified by a teacher telling a student “your knee pain is caused by your tight hips”, and to then prescribe a set of supplementary “hip opening” exercises to be done in conjunction with the regular asana practice. I’ve seen numerous practitioners who believe that “opening the hips more” or “opening the shoulders more” will be the cure to all of the issues which they face in their practice. I am frequently asked by students who are struggling with some particular asana “which body part” is stiff or stuck or needs to open more, and is therefore responsible for their inability to perform the asana.

A more Eastern influenced form of reductionism would be to characterize all aspects of bodily pain, tension, or “blockage” as being psychological in origin. In this view, the mind is seen as being the root cause of all bodily experience and any pain in the body is reduced to some dysfunction or blockage in the psychological realm. The poor student is then left to haplessly believe that their bodily torment is due to some mental issue which they have no real way of addressing.

The key theme in all of the above examples, is the reduction of the holistic experience of the state of a person’s body-mind to a single root cause, and then to assume that the holistic state of the person’s body-mind can be “fixed” by simply changing or fixing that one root cause. This is the essence of reductionism.

A human being is an extremely complex system. There are 11 organ systems in the human body (skeletal, muscle, nervous, integumentary, endocrine, circulatory, lymphatic, digestive, respiratory, urinary, reproductive), as well as various layers of “non-physical” experience, such as the cognitive, emotional, energetic, etc. All of these systems and layers of a human being are interconnected and coordinated in an unfathomably complex network of dynamic relationships and feedback loops.

When this human body-mind system places itself into the transient postural states of a particular asana or vinyasa, there will be an effect of all of these physical, and non-physical systems of the human being, as well as in the network of connections and relationships between all of these systems. The overall effect is a shift in the entirety of the state of the human being. This shift in the whole being is known as an “emergent property” and it cannot be explained by looking at the properties of any of the component body-mind parts, or by looking at how the asana affects any of those single component parts. Emergent properties of a dynamic and complex system literally “emerge” out of the complex dynamics of the relationships between all of the component parts. The key point to understand is that the emergent characteristics of the whole are a result of the properties and dynamics of the relationships between the parts. The emergent characteristics of the whole are not features of the parts themselves. These emergent features can only be understood by looking at the system as a dynamic whole.

A single Ashtanga series, from ekam position of surya namaskar A up to utpluthi, should also be thought of as a system. Practicing any of the Ashtanga series in their entirety will give certain effects, features and results, which cannot be found or explained by looking at the characteristics any of the individual asanas in that series. They cannot even be explained by looking at all of the individual asanas in the series. The effects that one experiences by practicing a particular Ashtanga series are emergent properties which emerge out of the relationships between all of the asanas and vinyasas in the series taken together and they can only be understood by perceiving the series as a complex and dynamic system which is a whole in itself.

A system can vary in its relative stability. When the dynamic relationships between the parts of a system are changing or shifting significantly – such as when the long term postural tendency is undergoing significant shifting – the system can be said to be unstable and in a state of transition. Whatever emergent features – such as pain – the system is experiencing at that time should be thought of as properties of the whole system, not properties of any of the parts of the system. The pain is a property which emerges out of the restructuring of the relationships and feedback loops between the parts of the system, as the system transitions from one structural state to another structural state. The pain is not a symptom of any one root cause or “dysfunction” of any component part of the system.

I suggest that in many cases of pain or discomfort experienced through long term Ashtanga practice, adopting this perspective is the most accurate way of understanding and dealing with what is taking place. The system of the Ashtanga series is exerting an effect which is causing a shift or change in the tensegrity dynamics of the relationships between the parts of the system of the whole human being. The pain is something that emerges out of the shifting of this complex and dynamic set of relationships. The pain is not a property of any one part of the system and should not be attempted to be addressed through a perspective of linear causation.

This brings us back to the quote from Alf Nachemson which I put at the beginning of this article. No matter how learned one may be in anatomy and physiology, I don’t think that anyone can conclusively say that they understand exactly where a person’s pain is coming from – especially in this type of situation. This is because the pain is not due to any one root pathology in any one part of the body. The pain is simply a reflection of the shifting relationship dynamics between all the parts of the whole human system. How these patterns are structured, and how they are changing, is far too complex for any human mind to completely understand.

The resolution to the pain necessarily involves retaining a systems perspective. In cases of “transformational pain”, the system of the Ashtanga series should continue to be practiced with as little modification to the dynamics of the system as possible. This way, the inputs that the practice is exerting on the human system remain consistent, and the intelligent reorganization process which the practice is inducing retains some stability. The human body-mind system will eventually imbibe and embody the transient daily inputs of the Ashtanga series in the more stable long term postural state which it is moving towards. Continued intelligent movement will resolve the pain. Restriction and reductionist oriented intervention probably will not.

In my 18 years of daily yoga practice (14 of which have been Ashtanga), I’ve gone through many periods of pain, which have lasted anywhere from a few days to the better part of a year. Some of this pain has been severe, and accompanied by serious mobility restrictions. In most cases, these periods of pain were a by-product of a deeper restructuring/recalibration of my body’s relationship to gravity, as I have described in this article. Most of the time, the pain could be localized to a general area of the body, but usually not to a specific structure (ie. a particular muscle, tendon, bone, joint, etc). My approach to dealing with these periods has always been the same: Pull back to a more basic version of my daily practice. Often this would mean a less advanced series, or even a partial series. I would practice as much of the series as felt energetically sustainable, even if it was still accompanied by pain or discomfort. Often, my decision on which series to use “therapeutically” or how much of the series to practice was intuitive. I find that decisions based on systems thinking often feel more intuitive, because they require a different form of cognitive understanding than the more analytical reductionist approach which we are habituated to in most modern societies around the world. Generally, if I had to modify more than one or two postures or vinyasas in that series which I had chosen to practice, I would stop my practice at that point and go into the finishing sequence. Using this method, day by day and week by week, I would always see a gradual improvement. Improvement is defined as an increase in mobility and a decrease in pain and (equally importantly) an increase in a sense of confidence and mental/energetic stability and vitality. This could also be simplified by saying improvement is defined as a movement towards stabilization in both body and mind. As my condition improved, I would add postures and series back to my practice until I arrived back at my standard normal practice again. Some days, it might be just one inch more of space in one particular posture that could be taken without inducing pain, but if I paid attention, there were always some signs of improvement and usually on a daily basis. The pain would often move around, shifting to different places in my body, spreading out, until eventually it would disappear completely. Other times, it would happen more dramatically. I have had experiences where very serious pain completely vanished from the body instantaneously, after performing a particular posture or movement in the course of my practice that day. Whether the “recovery” was gradual or sudden, the technique was the same: careful, aware and embodied movement, to whatever degree of capacity I had at the time, encouraged and actively led to the eventual resolution of the pain.

One particularly interesting experience came during my first few months of my Ashtanga practice in 2004. I had a lot of energy and enthusiasm at that time in my life, and I was practicing with an older style teacher who generally didn’t stop practitioners at the asanas they couldn’t yet perform fully. Due to my Iyengar background, I could already do many of the postures, so within a few months of beginning Ashtanga practice, I was doing all of primary and all of intermediate series as a 3.5 hour daily practice. Needless to say, I was in a significant amount of pain and experiencing dramatic structural changes. I watched the coming and going of different pains and the resulting structural shifts in my body with great interest and curiosity.

When I had begun practicing Iyengar yoga some four or five years prior to that, I learned how to practice dropping back from a standing position into a backbend on a beach in Northern Goa. I wasn’t ready for that movement, but after watching a flexible girl in our class do it, I wanted to try. My teacher obliged and encouraged me to try. Through sheer will power, I managed to arch back and land successfully in a backbend. It was exhilarating and empowering. Two days later, when our class was “working on” backbends again, I wanted to try dropping back again. I managed to succeed, and this time my teacher came over and pulled me back up to a standing position. We went on to practice standing postures, and I felt a pain in between two vertebrae of my lumbar spine. The pain grew stronger over the course of that day and ended up staying with me for the rest of my four month stay in Goa that year. It also brought up a lot of negative emotions. Eventually it resolved itself completely.

During the first few months of my Ashtanga experience in 2004, my nemesis became kapotasana. It was very difficult for me to catch my heels, and every day when I was about to arch back into kapotasana, my teacher would appear in front of me and pull my hands directly to my heels from the air. It was always terrifying, but once it was done it felt exhilarating. It happened every day. My teacher could be on the other side of the room as I was preparing, but as soon as I started to arch back, he would magically appear in front of me and pull my hands to my heels. The transformative effects of the practice on my entire being during that time were profound, and that one particular daily experience of kapotasana seemed to be at the heart of everything that was going on. Sometimes, I would sit in meditation later in the day, and spend an hour with my eyes closed, meditating on my experience of kapotasana. Over and over again, I would replay in my mind, in my nerves, and in my body what it felt like to have one hand, then the other hand on my heels, my elbows down and then…boom…that rush. Like a tape looped on repeat, over and over again. It was all part of the deeper integration of the experience into every layer of my being and the transformative process that was taking place.

Eventually, I started to feel some minor back pain between the same vertebrae that I had hurt years before in my Iyengar beach drop-back experience. Day by day, the back pain grew worse. I began to reexperience the same emotions which I had felt when I hurt my back in Goa, and I grew increasingly fearful and anxious when I prepared for kapotasana each day. Still, the energetic rush that ensued after being pulled into kapotasana made it all okay. One morning, I woke up and my back was very sore. It felt exactly like it had after the injury in Goa, and I also felt very depressed. “Great”, I thought. “I’ve arrived back here. At least four months of back pain….” I forced myself to go to class and practice, but I made a strong and solemn determination that I wouldn’t perform kapotasana for some days. “When he comes over, I’ll tell him I can’t….”

I kept an eye on my teacher as I practiced the postures leading up to kapotasana. Sure enough, when the time came he appeared in front of me. “No, no, not today”, I said firmly. “Just go. Breathe”, he replied. “No, my back, it really hurts…”, I said. “Go!”, he commanded impatiently. I sighed and started to arch. I felt the familiar pain between my vertebrae and he went to grab my first hand to pull it to my heel. I panicked and managed to yell out, “No!” I resisted his pull and tried to come back up. “Shut up and breathe, don’t cry”, he hissed from above me. He kept pulling and I panicked even more and started flailing around until I had wormed my way out of the posture and out of his grasp and collapsed in a heap on the ground. It was such a scene that everyone in the room had stopped practicing to look over and see what was going on. My teacher stood over me shaking his head disappointingly. Another teacher who was practicing close to me called over, “He needs to squeeze his legs more so that he doesn’t get back pain.” My teacher looked up and responded loudly so that everyone could hear, “Huh! There’s nothing wrong with his legs or his back, he’s just got a WEAK MIND today, that’s all.”

His technique worked. From my collapsed and disempowered state of body and mind on the ground, I suddenly felt a rush of anger and energy surge through me. How dare he call me weak minded! I’ll show him! I quickly got back up and muttered “All right, I’ll do it!” He smiled amusingly and stepped back to watch me. I took the preparatory position and unhesitatingly started to arch back into kapotasana. Instead of fear and trepidation, I felt a strong sense of pride and confidence. There was no back pain and I reached back and caught my heel with my first hand without help for the first time ever. My teacher then stepped in and gave me a tiny bit of help on the second hand. I put my elbows down. “See?” He said from above, “Now what was all that crying and fussing for?” The pain between my vertebrae had completely vanished and it never returned.

The above example is dramatic, and I certainly don’t recommend or apply these kinds of methods in general. Nonetheless, it shows how quickly and suddenly the tensegrity state of a system can shift and change, and how many different factors there are which contribute to the internal relationship patterns in a particular state of body-mind. In this particular case, the shifting of a mental and energetic perspective contributed strongly to the crystallizing of a new and healthier physical structural pattern in my body.

Movement heals. Fear and limitation do not. I’ve also experienced this outside of the yoga practice. When I was in my early 20s, before I had started practicing yoga, I injured my left groin while on a multi-day backpacking trip. A friend and I were attempting to cover what seemed like a never-ending amount of distance over a particularly challenging section of terrain on the West Coast of Canada. We had already taken several hours longer than we had anticipated to cover the distance required to arrive at our next destination. The only way I could will my body to keep going was to imagine that my legs were like powerful pistons, pumping up and down into the earth. Somehow, the image allowed me to ignore the muscular fatigue that had set in long before. We finally arrived near dusk at the beach where we were to camp for the night and we both threw off our heavy packs and collapsed in a heap on the ground. We lay still for a long time, enjoying the flood of endorphins rushing through our systems. When I finally got up some time later, there was a deep ache in my left groin. The pain got worse as the evening went on, and it was still there the following morning. I had no choice but to strap on my pack and walk again the following day, as our feet were the only way to get back to civilization.

The injury stayed with me for some time, and I began to grow concerned. I had plans to soon embark on my first trip outside of Canada, and I had a flight to Indonesia booked for a few weeks later. I’d never experienced such a persistent pain at that point in my young life. Eventually, I went to see a doctor. The doctor didn’t order any scans or tests, and after a brief examination told me that I would be fine in 6 – 8 weeks. I expressed my concern about my upcoming trip to Asia, as I planned to be very physically active. I wondered out loud whether I should “limit myself and rest more”. The doctor grinned broadly at me and replied “Iain – Never limit yourself, you’ll be fine.” Those words had a powerful healing effect, and filled me with confidence. I went home in a good mood and happily continued to plan for my trip. Though the pain was still there, I no longer focused on it or thought about limiting myself because of it. A few week later, I had landed in Bali and the pain in my groin was completely gone.

Over the next months, I traveled through several of the Indonesian islands and eventually flew to India and began to travel around the subcontinent. I kept up my usual habit of vigorous physical activity, and the groin injury seemed to be a thing of the past. I never thought about it. I eventually wound up in Hampi. One day, I was lying on one of the giant boulders in the late afternoon, enjoying the sensation of the heat that still radiated out of the sun-warmed rock and into my body, even though the sun had faded into the horizon some time earlier. I was completely relaxed and at ease and peace. Suddenly, I felt a “sproing” in my groin and the pain returned, just like that. I was stunned. I hadn’t been very active at all that day, and in the moment that the pain returned, I was lying down, completely relaxed, enjoying a nice heat radiation massage from the rock. I walked back to my guest house worried, and my concern grew as the pain persisted over the next few days.

I immediately defaulted to the dogma of limiting my activities again, figuring that resting my body would be the wisest thing to do. I decided to make a beach my next destination, where I could really relax. I had plans to go to the Himalayas a short time later, where I hoped to do a lot of hiking in the mountains. I also had plans to return to Canada following that, where I would work as a treeplanter for several months, saving up enough money to travel again the following year. Treeplanting had been my main source of income for the preceding 3 or 4 years. Treeplanting in Canada is a particularly intense and grueling job, both physically and mentally. It involves living in a tent in the Northern Canadian wilderness for months at a time, spending 10 – 12 hours each day planting saplings in areas that had previously been logged. A good planter could plant up to 3000 trees every day, and earn a decent amount of money doing so. Of course, to do this required a healthy and strong body. An injured leg would be a big obstacle to my plan.

I took my plans to relax on the beach seriously, and for one month I did extremely little aside from lying around, and occasionally swimming. The condition of my leg changed very little during this time. I was growing more and more worried, and pictured myself returning home with very little money and an inability to work at my job of choice, which was necessary to continue with the lifestyle I wanted to live. It was not a happy vision. My anxiety around my physical condition grew.

Eventually, I decided to travel up to the Himalayas even though I didn’t feel much better. The hot season was setting in, and I wanted to move to a more comfortable climate. I stopped in New Delhi on my way up and visited a doctor. The doctor gave me the standard advice of resting completely and taking painkillers. He was quite adamant about his advice and I left his office feeling even worse. I ignored his advice and carried on up to Dharamsala and made my way up to Dharamkot village, where I would ultimately spend the better part of the subsequent two years.

Dharamkot village is perched on the side of a steep mountain, and at that time was accessible by foot path only. Moving anywhere, for any reason, meant walking up and down the steep slope. I was pleasantly surprised to find that my leg felt no worse for this dramatic increase in activity. The mountain environment was fresh and intoxicating to me and I was filled with vitality and energy and a desire to hike and explore deep into the mountains. I began to gather information about some of the nearby trekking routes, while also bitterly reminding myself that I was in no shape to tackle them.

After some time, I heard about a famous practitioner of Tibetan Medicine in Dharamsala named Yeshi Dhonden. Curious and hopeful, I went to his clinic one morning, took a number, and sat in the crowded waiting room. When my turn came, I went in to see the doctor. I described my groin injury to him via his translator, and he took my pulse and then placed his fingers on my groin. “The doctor has found a lump”, reported his translator. “A lump?” I asked. “Yes, an energy lump, something is blocked”, The translator replied.

He wrote a prescription for a collection of Tibetan herbs, dried and rolled into little pill shaped balls, gave me instructions on how to take them and to return for a check-up in two weeks time. He also adamantly explained “And – You must remain VERY ACTIVE while you are taking this medicine!” “Active?” I asked, “Like, walking?” “Yes!” he replied, “You must walk a lot. This will keep energy flowing into the wound, and the medicine will work much better.” I couldn’t believe this wonderful news. “Can I go trekking up the mountain?” I asked. “Oh yes”, he said, “That would be very good.”

Just as when the doctor in Canada had told me not to ever limit myself, I left the clinic of Yeshi Dhonden in a wonderful mood. I felt empowered and confident. I had my bag of Tibetan pills and immediately made plans to go trekking up the mountain. I spent the next six weeks in Dharamsala, hiking, trekking, and also practicing yoga for the first time in my life. I visited Yeshi Dhonden for a check-up every two weeks and would receive a new bag of herbal pills and the news that the doctor was very happy with my progress and that I would soon be completely cured. By the time I flew back to Canada, with enough herbal pills to last me for another month, the pain had vanished. When I started the difficult work of treeplanting a short time later, the pain reemerged briefly and jumped from my left groin over to my right hip for a days, but then it disappeared and never returned, and I continued on my journey as planned.

I graduated from Systems Design Engineering.

One thing that we did study with systems is that you can look at systems from various levels. While I will defer to you with respect to injury and the ashtanga system, I will say that you can break systems down meaningfully. You do so by breaking systems down into smaller systems. The smallest possible system is a relationship between two clearly defined “things” (or “ideas”.)

In electronics we had to study a particular system (say a circuit board) from two views to get a complete understanding. (We did the same learning how guns worked in the army).

One view is the component view. This is the components in isolation. Looking at a particular integrated circuit chip we could look at all the different inputs and outputs (and operations) that this one chip can do.

This is its’ potential, the view across time (and if time where a spiraling wav form traveling though space, this would be the view of time while standing off to the side, watching (the sinusoidal view)). This view might also be called the “architectural” view. It’s the elements of a system but not how they work together. It’s the view of all the parts of an engine that’s been taken apart

The signal view is the view as the system is working. Studying a system we’d trace one signal at a time through its unique path through the system. Then we’d study all other signal flows. This is the view while riding the wave of time. This is the view when potential is realized.

It’s the equivalent of putting a battery in a circuit and turning the circuit on so that current flows from the battery and back into it.

For any complex system, it’s possible to break it down into smaller systems and study the emergent properties of these smaller systems. The emergent properties of the smaller systems then create the emergent properties of the larger system.

While in a lot of cases its not possible to precisely model a complex system, it is possible to get a sense of it from it’s smaller sub systems.

Do you need to break a system down into smaller systems?

It depends on your goal. A driver doesn’t need to know how his or her car works in order to drive.

But a mechanic does.

A designer does.

If you are designing your own yoga practices then it helps to understand how a system works and why it works from a number of different view points so that you can design your own effective systems.

If you are modifying a sequence, say for someone who can’t do certain poses, it helps to understand the system so that you can modify it effectively.

But that’s just my take on it.

Thanks for your comments and explanation, Neil.

I understand what you are saying. The universe is basically composed of systems nested within system. Each system is composed of sub-systems and each system is itself a sub-system part of a larger system. For example, Gaia is composed of ecozones, which are composed of ecosystems, which are composed of organisms, which are composed of organs, which are composed of cells….. . Each layer is it’s own system, and of course we could continue to stretch the nesting of systems within systems in both directions.

I also agree that there is value in looking at, and understanding the component parts (or sub-systems) of a system in isolation from the system itself. My understanding of systems sciences is that they look at both the parts and the whole simultaneously.

The way I see it, we have lenses of different focal power. One lens would analyze the system as a whole. Another lens would analyze the sub-systems it is composed of. Another lens could analyze the sub-sub-systems, and so on. As you said, which lens is most appropriate to use would depend on the question being asked, or the problem we are addressing.

In terms of “transformational pain”, which was the main theme of my article, I don’t think the reductionist approach of looking at the sub-systems in isolation from the whole is effective or very helpful. But, there are other situations where it could be. The problem is, most people default to reductionism, or examining the properties of the component parts (or sub-systems) because they expect to find a “root cause” which is more fundamentally real than the emergent properties of the whole. In my article, I was attempting to point out the drawbacks in this default approach, especially in the case of transformational pain in Ashtanga practice.

A final point is that I think there is a big difference between “artifical” ( ie. man-made) systems, such as electronics, which are designed with a particular function and purpose; and systems which spontaneously occur in nature as self-organizing or autopoetic life systems. I think the later are much more difficult to predict based on understanding their component parts or sub-systems. For example, if we were to make an experiment where we took 50 random types of living organism and a set of inorganic materials and a set of environmental conditions, and threw them all together, would we be able to predict the emergent properties of the resulting ecosystem, even if we knew everything there is to know about the component parts? I doubt it. We could make educated guesses, but they would be just that – guesses, because there is an inherent element of randomness in how the relationships between all of these sub-system parts would interact and develop over time.

p.s. enjoyed your personal experiences of being strong minded in particular.

I’ve had similiar experiences where simply changing my mind changed the way that I did the pose.

Thank you for your in-depth presentation of your methodology and analysis. So well written and though out. One addition I may suggest is recognizing that during this healing process the use of supportive aids such as hot Epsom salt baths, regular therapeutic massage, and an anti-inflammatory diet are helpful to support the practitioner through the “symptoms” of the healing process as they arrive. Of course, deep sleep is also essential for repair of the body and peace of mind. Thanks again.Pamela Hollander (studying/practicing since 1964, started practice with Tim Miller and Sri.K. Patthabi Jois in 1993).

Thanks for your comments, Pamela.

I agree that lifestyle factors are extremely important in supporting the transformative process of the practice. Diet and lifestyle is a topic that I have also been planning to write about for some time.

I have found a lot of benefit in transitioning to a more ant-inflammatory diet over the past 10 years or so. It helps quite a bit in muscle recovery in general and especially when one is going through painful periods. I think eating a more alkaline diet is a key factor, as well as getting enough of all the necessary nutritional elements to support both the removal of waste products, and the rebuilding of muscle tissue. I have much more to say on this topic….hopefully soon.

Salt bath are great. I used to use them regularly (I don’t have a bathtub here in Bali though). Sea salt and rock salt are also good in a bath. Clay baths can be good too.

Therapeutic massage is debatable. I know some practitioners feel they benefit from it, but I find it disruptive to the tension patterning in the body. The way I see it is that most types of massage will remove tension from the system, and I usually feel good immediately afterwards, but the following day my body and practice are a mess. My internal structural integrity usually feels very off and I am also extremely stiff the morning after a massage. I feel it is because the massage has also removed “healthy” tension – (ie. tension that is functional and supporting the structural patterning), along with the excess tension (ie. tension that is not functional and needs to be released). The result is a lot of confusion in the internal bodily intelligence. I think it confuses the restructuring process. Sharath also recommends against massage. Anyone who has practiced in Mysore in the past few years has surely heard Sharath’s African massage story. BKS Iyengar also mentioned in one of his books that he feels massage and yoga are incompatible. I think the exact quote was something like “If you do some good yoga practice, and then have a massage, the next morning you’ll wake up like a dead person.”

I do find “abhyanga” – applying of oil to the body before bathing – to be quite helpful. When I am anywhere that is not a tropical climate, I do this on a daily basis. The application of oil, followed by hot water shower or bath has an anti inflammatory and lubricating effect which is beneficial. The traditional Saturday morning castor oil bath is also very helpful, but I don’t usually use this as it is too messy.

Sleep is also important, though I find that multiple periods of shorter sleep is better than one chunk of long sleep. Taking a long savasana (I like to have 30 minutes savasana) after practice, and even again later in the day is also extremely important. It is when we are at rest that the organic intelligence processes the inputs of the practice and integrates the restructuring more deeply. In general, if the body needs more sleep during these periods of deeper transition, it will ask for it, and we should allow ourselves to rest more.

Thanks again for your input and reminder of these important factors.

Hi Iain,

Many thanks for this amazing article which I totally agree with, both from a professional view and from personal experience.

I’m a physical therapist who has studied biomechanics. Now in my fifties, I have been practicing ashtanga for a number of years. Last year, following the recovery from a severe motorbike accident that resulted in multiple injuries, I returned to practice and did a month intensive with Iain in Bali. Pain felt its constant presence and often overwhelmed me, physically and emotionally. Many times I felt like giving up.

As a therapist it is my experience that in these times of hyper-connectivity to internet, everyone tends to rationalize symptoms and seek answers to their ailments online without proper understanding of the “systems” that our complex evolutionary journey has allowed us to build. We oversimplify, and we want things to be fixed. A quick fix is also what tends to be expected of the professionals in the medical field.

The fact is, as described here by Iain, the underlying processes are complex and the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Psychological factors affect the process greatly but cannot be simplified or analyzed just by intellectual rationalization. We need to learn to let go, to trust the innate and instinctual intelligence of our body and listen and respect the healing process that are in motion. Pain is part of the living process and our best teacher.

Hi Max, it’s great to hear from you. I appreciate your insightful comments and I agree with everything you have said here, especially regarding the influence of hyperconnectivity. Keep in touch and I hope to see you again in Bali!

Dear Iain,

thank you for writing this blog and sharing your experiences. When I see how long the post are, I usually want to stop reading after a while, but I always keep going, because I find it very interesting.

I’m relatively new to yoga and even newer to Ashtanga yoga (2.5 years) and atm trying to build up a regular practice. For the past years my shoulders have been irking me and, even though the pain lessened significantly through the practice, I find that positions like Maricyasana can bring that feeling of instability back. I’ve been getting ergotherapy on a regular basis for half a year now, tackling the shoulders, and have started leaving out bits of the practice or even not practising Ashtanga for longer stretches altogether. So I’m in a bit of a rut.

Reading about your pains and how you have worked through them and kept on practising regardless, because the body cannot restructure itself without constant practice and some pain, just gave me a different perspective and I am now motivated to start again, properly and more regularly – without leaving out postures.

Also, thank you for the comment about massages: When my shoulder pains started (so severely that I started to have trouble sleeping) I first tried massage, but did not have the feeling that it actually accomplished anything, apart from pleasant sensations as long as it lasted. Permanent relief only came through the practice. I found it interesting to read that Sharath and Iyengar advise against it, because rading that resonated with my experiences.

Looking forward to the next article!

All the best,

Kristina

P.S.: Can something maybe be done about that sidebar with facebook, twitter etc. symbols? I always read your blog on my tablet and the sidebar blocks the first two letters of every line, which is very irritating and makes reading harder. Maybe that can be solved by moving it to the right side?

Hi Kristina. Thanks for your comment and for sharing your experiences. I’m glad to hear they resonate with what I have described in my article. Sorry about the sidebar. On my laptop and phone they don’t obscure the text, so it must be something with tablets. Social media is currently the best way to spread my writings around, and having the sidebar there does lead to more shares, so that is why I have it. I can look into whether it is possible to move it to the right side.

You can close that bar. There is a little tab at the bottom of it. I agree it is highly annoying

Hey! Can you give some more details on your 3.5 hour primary and intermediate practice? I have 4 months off from work this whole summer and I was wondering about this. I am 23, been practicing for 3 years and can do all of primary, and do most of intermediate series with a few lower progressions in three moves. Would it be beneficial to try doing both practices?

Hi Theo. I’ve practiced two full series consistently, for a few months at a time on a few separate occasions in my practice history. It can be beneficial, if it fits in the practitioner’s life in a way that is not overly consuming. It should be built up gradually, as part of the process of adding on postures in a new series that one is learning. Then, instead of splitting the new series at the normal point, one simply keeps adding on postures and practicing both series. I’d also say that one should ideally follow the “modern” method, where each posture should be “mastered” or effectively integrated before moving on to the subsequent posture in the adding on process. If one begins to feel excessively depleted, irritated in the nervous system, or begins to experience excessive pain, it would be more appropriate to split and go back to a single series practice. What it is appropriate or not will always depend on each individual case. Hope that helps!

Hi Iain! Thank you for one more super-interesting article.

I’ve been practicing regularly Ashtanga yoga for a year now. I’m 41 years-old and I feel great as I go through the first series.

The reason I write on this article is because I would like to ask your comment regarding injuries on long-term practitioners.

For example, I recently read an interview where Jessica Walden generously shares her life, and talks about her spine injury (interview here: http://www.ashtangaparampara.org/jessica-walden.html). She found out that she had a particular condition in 2001 and still she decided to keep doing her practice believing that yoga would heal her. The injury happened in 2013.

There is another similar story from an ex-ashtangi but I will not reference here.

As for me, I only can tell that I’ve been feeling a pinching pain in my right knee for some months now, and sometimes I really don’t know if I should rest or should negotiate with the pain in my daily practice.

Also, would like to know your opinion, as a teacher and practitioner, if there is a mid-point or a particular state of mind from which you can confidently listen to your body. As I read in your story, your teacher teased you and messed with your ego, and that’s why you decided to go forward with the backbending. Is it a safe strategy, to rely in your ego when you don’t feel up to the challenge?

Hi Luis,

It is difficult for me to make specific comments on injury, as each situation is different. I would also find it inappropriate to comment on an injury experienced by a practitioner that I haven’t specifically known or worked with personally. Without seeing a person practice, it would be highly conjectural to make assumptions, and I think somewhat unethical. I wrote my article in general terms, and leave it up to each individual to asses how it applies, or doesn’t apply to their own particular situations.

To view all pain or injury as a normal or healthy part of the restructuring process would not be correct. Poor alignment, excessive pushing or overpracticing, unfocused or disembodied practice, etc., can all lead to experiences of pain which could have been avoided and are not necessarily part of a healthy restructuring process.

Regarding Jessica’s interview, she seems to have a very balanced understanding and perspective on exactly why her injury occurred, and I don’t know her, so it wouldn’t be appropriate for me to add personal assessment. Some of the factors she listed, such as having a previous structural condition, blind faith in the practice, and being exhausted at the time the injury occurred are all key points. It is encouraging to read that she did not give up, or “blame” the practice itself and that she used the practice as part of her recovery process in a way that is consistent with what I described in my article.

I know there are some other outspoken practitioners who suffered grievous injuries through the practice and as a result they no longer practice Ashtanga. I have read about cases like this, where the descriptions of their practices make it very clear to me that these people were not using the Ashtanga method correctly and I would say not even really practicing Ashtanga Yoga, rather they were practicing their own hybrid form of yoga. They were experimenting on themselves and it went bad, but rather than taking responsibility and ownership for their failed experimentation, they choose to blame the practice itself.

As for your last question, one should always endeavor to practice in an embodied state which utilizes the organic, animal intelligence of the body and the nerves as the prime authority and decision maker. The body knows what is good and what isn’t good for it. It knows what is and what isn’t possible. That is why animals make very few mistakes in their movements in nature. If we learn how to move as the phenomenologically experiencing body, rather than as a set of intellectual ideas, them we will usually make the appropriate decisions, and I encourage people to try to practice this way. Sometimes, we need a good teacher to help us access that state of intelligence.

Hello Iain!

Your article came at the perfect time as I am currently dealing with a groin injury/lump. I have been able to do baddha konasana and get chest to feet chin to floor with assists and had no problems in my groin. Then i started to get a twinge in my left groin too and I couldn’t do baddha konasana. I went to work and got up quickly from my chair and something must have teared in my inner thigh as I had a huge bruise the following day. But as I have been working on baddha konasana, it has been painful but through every assist it has helped to release the tension there and have slowly gotten my knees back to the floor. However today I felt a twinge like I did before and after practice felt a lump there again and similar discomfort as I did before the muscle tear. You said for you it was a blockage. I feel this is similar for me…I am starting to feel slight anxiety in this posture as I don’t know how far to go. as I have worked through the pain it has given me release and flexibility in that area, but this lump coming back again makes me feel different about it again. I have also started to feel slight pain in my left knee too, I don’t know whether this is pain moving around too (like your describe in your article). Thank you for your article it has made me look at pain in a different way, I am truly grateful!

Hi Amy,

I’m glad you found the article helpful. I don’t like to give specific advice over the internet, but it does sound like you should probably back off and ease up in your practice until things start to feel better. If you are experiencing persistent pain in one area during a particular posture, you probably shouldn’t be adjusted deeper into it, beyond what you are capable of doing on your own. When working on your own, I would only go so far as you start to feel the pain, and resist trying to move further into the posture until the pain starts to dissipate. It can take time for the body to integrate deeper changes, and a healthy sense of restraint becomes necessary with long term practice. Best of luck with it!

Hi Ian,

I think the teacher who made you practice Kapotasana eventough you had pain was ‘Rolf’..

He injured me so severely that I couldn’t even get out of the bed for days and barely could walk for many weeks. After 10 years, it is still a gift that I carry on my spine.

This injury is his Karmic dept. I still am going through my process to forgive him.

How on earth one person could have the right to do this to another one ?

Same day there was another poor guy , who was also crippled and on a lot of pain.

Only the lucky ones survive. I am glad to hear that you are one of them. There are so many people who got injured by those harsh adjustments.

It sounds very new age to suggest that ‘they have weak minds’ or stuff like that.

All the best,

Hello Maya.

Rolf is not the teacher I was referring to in this particular story. I am sorry to hear about your bad experience though.

Inappropriate teaching methods can certainly be harmful. It is also important for students to be clear on their own limitations and boundaries in the student-teacher interaction. I can’t comment on specific incidents that I was not there to witness or be a part of. I can only comment on trends and patterns in my own experiences and experiences of others that I have directly witnessed.

All the best to you

Iain

Dear Iain,

Thanks for your informative article, I enjoyed it. Last year I tore my left medial meniscus during practice. I ended up having both knees imaged with MRI and it turned out that my right medial meniscus was also torn, but the symptoms weren’t as severe as the left. The left was catching when bent and I couldn’t do any seated postures. I had surgery within 1 month as I wanted to get back to a full practice. The recovery was hard, taking at least 6 months to get back to where I was before injuring the left knee. Now unfortunately, I think I may have torn the right meniscus. Again it’s very sore in seated posture and is catching when bent, I’ve stopped practicing to let it rest, but now I’m just so unsure of everything, I don’t want to go through the surgery again, but what I’ve read, the meniscus normally never heals. The most disheartening thing though is that since the surgery I have been very careful and mindful of any knee pain. I backed off every time. I’m so confused and am thinking should I just leave it and see if time heals, or the very least takes the catching symptoms away? Or should I walk away from the Ashtanga method alogethet, as I keep on injuring myself? Have you seen these type of reoccurring knee injuries?

What do you think?

Adam

Hi Adam,

Thanks for your comment. Sorry to hear about your struggles with your injuries. Unfortunately, I can’t give specific advice over the internet to someone I haven’t worked with. There are many factors which make each person and situation unique, and so I would need to work with you in person in order to be able to advise you on what to do.

In general, with that type of injury, you definitely should back off, as you have done. It certainly is possible to do a short and modified Ashtanga practice, but I strongly suggest that you seek a qualified teacher who understands the practice and your injury well, and to work closely with that teacher in person.

The final thing I can say, is that when one has a very strong desire to attain a particular posture, or level in the practice, that desire can obfuscate one’s ability to feel the intelligence of the body and to make appropriate decisions based on that intelligence. In all cases, I recommend trying to listen to the intelligence of the body, and make actions and decisions based on that, rather than based on a visualized goal of where one wants to be.

Lastly, you may find this e-book by Gregory Lehman to be helpful and interesting:

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57260f1fd51cd4d1168668ab/t/590dca266b8f5b01a7f97ceb/1494075961206/recovery+strategies+pain+guidebook+2017.pdf

Best of luck to you. Don’t give up and use the wisdom gained from you past experiences in moving forward.

Dear Ian,

Thank you so MUCH for this article. It is amazing! I am a Psychology student with a strong interest into Complex Dynamic System Theory (and some minor reservations about reductionism) and it’s application in Psychotherapy, as well as an Ashtanga Yoga practitioner. When I started practicing Ashtanga Yoga, I could immediately recognize the connection it has with my academic interests, but finding someone who thinks the same about it and who actually writes it down is super exciting for me. Is there any literature that you can recommend?

Funnily, I ended up here because me and my boyfriend were investigating the reason of a quite stubborn tightness around my left hip that is reoccurring. We were searching for the muscle that would most likely be the reason for the pain and uncomfortable feelings (including difficulties to gain full hip mobility in Padmasana, Marychasana etc.). Looking for the muscle that would most likely be the cause, did not work out really. Also, because the pain can only be pinpointed by using a lacrosse ball when lying in a specific position on the stomach and seems to be quite deeply rooted within the hip, so that it cannot actually be reached or located so easily. We kind of came to the conclusion, that it is most likely the result of many factors and also that there are probably many muscles throughout the whole body involved. My boyfriend added that since the pain is reoccurring that there seems to be quite a strong resistance (on a mental level) to change… I could relate to this in some ways. Now, after rationalizing quite a lot about the pain and tightness and reading your article, I really get your point. I think that most of us tend to think way too much about the details of the practice and physical sensations that arise with it. It seems entirely normal to experience uncomfortableness if practicing daily. Through the practice our system will certainly has to reorganize itself. There will be times where it will be stable and times where it will be less stable. But chaos is needed for a new organization to emerge so why bother so much about it.

Viewing ourselves as complex systems that are continuously changing is beautiful in many ways and definitely makes me accept my hip injury pain as simply being part of the processes.

Thank you so much for this great article.

Elena

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Elena. I am happy to hear that the point of the article resonated with your understanding and experience. Unfortunately, I don’t know of any other literature that specifically discusses the Ashtanga practice from a systems thinking perspective. My understanding draws from my own long term personal experience of the practice, integrated with my past studies (and continuing self-education) in the fields of psychology and biology – especially ecology and the emerging systems based approaches. Please do keep in touch and share any other ideas or thoughts you may have in this realm, as I am always happy to discuss and collaborate.

I’m in love. Thank you.

[…] through the sequential learning of the asanas and vinyasas of the Ashtanga system. In my article “A systems thinking perspective on the resolution of pain in Ashtanga practice”, I describe the restructuring process in more detail. The long term process of changing how the […]